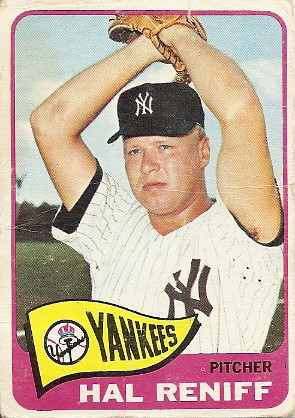

On to the next batch of cards, a ten-spot that was donated by reader Rick, who collects vintage cards from the 1960s and 1970s and prefers graded. More power to him - it would be a boring hobby if everyone was interested in the same things!

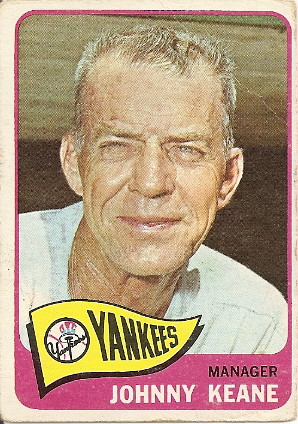

We haven't had a manager card for a while. This crusty customer is

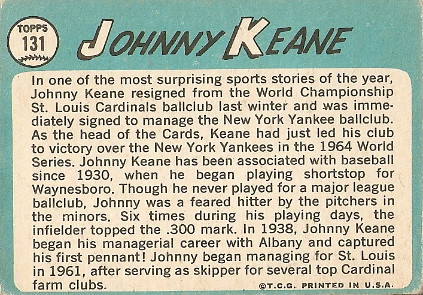

Johnny Keane, brand-new skipper of the Yankees. But it was a long, winding path to the top for the former minor-league shortstop. A St. Louis native, Keane played in the Cardinals' farm system but never got to the majors. A beaning caused a head injury that hastened the end of his playing career, and in 1938 the 26-year-old got his managerial start at the very bottom, managing the Cards' Class D team in Albany, Georgia. In his two years with the Travelers, he won two league championships, and he was on his way.

Keane gradually climbed the ladder in the Cardinals organization, spending 17 years plying his trade at outposts such as Mobile, New Iberia (Louisiana), Houston, Rochester, Columbus, and Omaha. His cumulative won-lost record was 1,357-1,166. He won four league titles, and took a dozen teams to the postseason. In 1959, St. Louis finally promoted him to the big-league coaching staff, a job he held for two-and-a-half seasons. On July 6, 1961, with the club languishing in fifth place at 33-41, manager Solly Hemus was fired and the 49-year-old Keane was tapped to replace him. He sparked the Cards to a 47-33 finish, which wasn't enough to pull them out of fifth place. Still, the team announced that Johnny would return for 1962.

Keane developed a reputation as a taciturn leader, but his fair treatment of young players paid dividends. Under his watch, the likes of Bob Gibson, Tim McCarver, Bill White, Curt Flood, and Lou Brock blossomed into valuable pieces of the Cardinals club. A mediocre 84-78 record in 1962 was a stepping stone to success; the following year, the Redbirds surged to 93 wins, playing runner-up to the 99-win Koufax/Drysdale Dodgers. That season set the stage for one of the more memorable efforts by a Cardinals team.

In spite of their talent-rich roster, Keane's Cards muddled through the spring and summer of 1964 and found themselves in fourth place on August 23, some 11 games behind the Phillies. On that day, St. Louis lost to the Giants, 3-2 in 10 innings, lowering their record to 65-58. Frustrated owner and brewing magnate August A. "Gussie" Busch, Jr. began cleaning house, possibly with the encouragement of recently-hired consultant Branch Rickey. Most of the prominent members of the team's front office were fired or forced to resign. Though Keane was spared, word leaked out that Busch had undertaken secret negotations with Dodgers coach Leo Durocher to replace the current skipper at season's end.

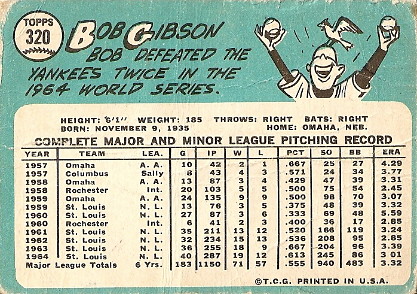

What happened over the course of the next month-plus was remarkable. St. Louis caught fire, winning 28 of their final 39 games (including eight straight at the end of September) to leapfrog three teams and win the National League pennant. The Cards spent five days in first place all year long; they were the final five days of the season. They finished one game ahead of the Phillies and Reds, and three ahead of the Giants, in a truly epic race. In the World Series (St. Louis' first since 1946), the Cards met the dynastic Yankees, who had likewise gone on a 28-11 closing run to vault past the Orioles and White Sox. It was a tense, back-and-forth affair, but the Cardinals emerged victorious on the strength of McCarver's bat (.478, 5 RBI) and Series MVP Gibson's arm (2-1, 3.00, 31 K/27 IP). But there was another surprise in store before the ticker-tape was even swept up.

When the Cardinals announced a press conference, most expected the team to announce a contract extension for Johnny Keane. Instead, the manager handed Busch and new general manager Bob Howsam his letter of resignation, which he had actually written in mid-September. Instead of hiring Durocher as previously rumored, St. Louis chose former infield Red Schoendienst as the new field boss. The runner-up Yankees scored a coup by hiring the man who had just beaten them, having rewarded first-year manager Yogi Berra for his 99-win debut by firing him in the blink of an eye.

Johnny started at a disadvantage in New York, inheriting an aging, brittle team. His strident approach was rejected by many Yankee veterans, and he often felt such pressure to win from day-to-day that he would press injured players into action too soon, causing them to miss even more time in the long run. As Jim Bouton put it in Ball Four, he was "willing to sacrifice a season to win a game". The 1965 Yankees fell to sixth place (77-85), and the following year lost 16 of their first 20 games. Keane was an easy scapegoat, and was fired and replaced by general manager Ralph Houk. In December of 1966, the ex-manager took a scouting job with the Angels. Just a month later, he died of a heart attack. Johnny Keane was 55 years old. Attesting to the morbid wonders of the Internet, you can see pictures of his gravesite

here.

Fun fact: Johnny shares a November 3 birthday with Ken Holtzman, Dwight Evans, and Hall of Famer Bob Feller.